Ned Chace was an American sailor who disembaked in Patagonia and there between 1898 and 1929, working on the sheep ranches (Estancias) in Santa Cruz province, Argentina.

His adventures were recorded in a book, which was published in 1931, based on lengthy interviews with him, by the authors of the book, after his return to the U.S.

Below I transcribe one of his amusing tales (which is very likely true):

"He [Chace] found a big encampment site where the trail passed [lake] San Martin between Kachaik and Frank's [...] different from any

modern Tehuelche encampment. It was fifty yards from water. He never found a modern toldo more than a few feet from water, even when the

ground near it was wet. 'This had been an Indian campamento that had been there for years, I should say, and it had been a big one. Here in the center it'd all been

covered about three feet deep with the loose sand and grass, and when the sheep come they cropped the grass, and the wind come and blew away the sand, leavin' a place where there'd been

fires, for where the ground had been burned it was red, and there'd been stones in the fire heatin'. And off a ways, two or three hundred yards, you'd find where different Indians had had their

tents around, and right in the center they evidently had that place where they'd all come to eat, settin' in a big circle. They had a fire in the middle, and then all these ostrich and guanaco bones

where they broke 'em to dig the marrow out right there and threw 'em behind 'em. Them bones was old, old, old. I suppose they was preserved in the sand. And then you'd find arrow-heads,

broken ones, it bein' I suppose where they took a broken one off to put on a new one. It was a great big circle, seventy-five foot across. [22.4 m]

Well, just off from this, there was a skeleton, right alongside a little fire where he'd died or been killed. The skeleton of a Christian with the legbones of a man

that must have been about five foot six and of a very slender build, but he had an enormous forehead on him and a proper well-formed under jaw and a narrow face. And

beside him there was a thin piece of steel about eighteen inches long, that looked like it might have been part of a rapier. That man'd never been buried. He was

either killed by the Indians and left alongside where his tent had been, or he was killed in the tent and they took him outside. His bones was lyin' out just on a level with

the fire, and they was Christian bones too you could tell they was different from Indian.'

He found a number of small encampment sites but never another big one." [1]

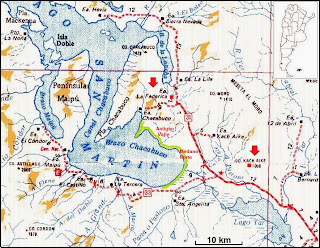

The map below shows the general area where Chace found this ancient native camp. The red arrows show the hill of Kachaik and Santiago (James) Frank's ranch, "La Federica", the

area shaded in green along the shores of Lake San Martín marks the likely location of the native camp. In red, the "Antiguo Valle" and "Médano Norte" sites.

Lake San Martín

First of all, let's get our bearings:

San Martín (named O'Higgins in Chile - both countries have this odd custom of giving different names to the lakes they share ) is a very large lake, shared by both countries: it has a surface area of 1,013 km2 (426 sq.mi.) of which 554 km2 are Chilean, and

459 km2, Argentine.

It is a low lying lake, barely 253 m above sea level (829 ft.), nestled among the high Andean peaks (+2,000 m - 6,550 ft.).

it is very deep: one of its arms, fjord-like O'Higgins arm is 836 m deep (2,741 ft.), making it the fifth deepest lake in the world. The others deeper lakes are: Lakes Baikal (1,741 m), Tanganika (1,471 m), Vostok (1,200 m) and the Caspian Sea (1,025 m).

The native Aonikenk Tehuleches called it Charre, which ment "Full". It was "discovered" by the Western world in 1877 by Argentine explorer Francisco "Perito" Moreno, who named it after Argentina's

national hero General José de San Martín, whose armies marched from the Pampas, across the Andes into Chile, Peru and Bolivia during the independence wars against Spain (1812 - 1824). By

the way, O'Higgins was his ally and colleague in arms in Chile.

It is a very irregular lake, with many long and narrow fjords, with steep sloped mountains towering over them; islands and Peninsulas mark its shores.

It receives the Mayer River on its northern arm and flows out, into the Pacific Ocean through the Pascua River. On the Chilean side of the border, the "Southern Ice Field" defines its

southern coast, with great glaciers such as the O'Higgins Glacier which calve icebergs into it.

The southeastern coast, in Argentina, is barren, lacking trees. A muddy stream from Lake Tar flows into the lake's Chacabuco Arm.

It can be reached from Argentina's National Highway No. 40 from the village of Tres Lagos by Provincial Highway No. 31, a gravel surfaced road-track.

Kach Aike

Chace mentions "Kachaik": it is a very conspicuous hill, on the right hand side of Highway 31, which juts out several hundred meters above the surrounding flat steppe.

It towers 1,008 m high (3,304 ft.), and is the remains of an ancient volcano: it was formed when the soft rock of the volcano's conical slopes was eroded, leaving the tough basaltic rock

that had solidified inside its chimney. The natives called the place:"Kach" = "ember" and "Aike" = "place".

The image below shows Kach Aike seen from the East, with the flat steppe and the lake behind it (the area where Chace found the native camp).

The "Ancient" natives

In Chace's story there are some interesting clues:

- The camp was buried by 3 ft. (1 m) of sand, which he said was due to recent sheep activity after the arrival of settlers (late 1800s) which destroyed the grass and allowed the Patagonian winds to remove the loose sand under it, thus revealing the site.

- "old, old, old" guanaco and ostrich bones.

- Arrow-heads strewn over a circle 75 ft. diameter

- It was a big and permanent camp quite far from the water 50 m (compared to contemporary Indian camps, which were very close to the water)

- A slender built skeleton with a thin piece of steel 18 in long (45.7 cm), probably part of a rapier. Bones which were "different from Indian ... Christian bones"

People have inhabited this area since 11,100 BP right after the glaciers retreated. This was followed by a period during which it was uninhabited (7,600 - 5,600 BP).

About 6,000 y BP the forest began at Chacabuco Peninsula, and the southeastern part of the lake was a grassland; then between 5,000 and 4,000 BP the area had more bushes and less grass.

From about 4,000 and 3,000 BP a wetter period began, which lasted until about 100 years ago. During this period a grassy steppe covered the area [2]. This was the grass cropped by the sheep.

Some archaeological studies have been done in that area [2]: One spanned the flatland next to Katch Aike, a plain formed by the glaciers, between Highway 31 and the lake, at the

Médano Margen norte (Northern Coast Dune) site. There they found lithic remains and guanaco bones in "four deflationary hollows" [deflation: where sand has been removed by the wind] "that covered

an area of 345 m2" [quite in agreement with Chace's definition of a "cleared area" where the sand had been removed, and also its surface area: a circle with a diameter of 75 ft. covers 410 m2].

Another site was found at "antiguo Valle" (Old Valley), to the nortwest, where the remains covered a surface of 600 m2.

In the map above I have shaded in green, the area where this campsite may have been located. It was 50 yards from the lake, Chace makes a point in saying that contemporary Indians never camped so far from water. The greater distance

may either indicate that the natives were not of the same group as the then extant Tehuelche natives or, that the lake level dropped moving the shore further away from the site during the period of time that has elapsed since the natives camped there.

I have not found any evidence that the lake's water level has dropped, but I will keep on looking for it.

The datings of occupations at some caves close by date back to 4,760 BP, and at Lake San Martin (Kach Aike) and Lake Tar, there are late Holocene dates (2,500 BP).

Interestingly, "protected places like the dunes, had been occupied all year round... added to this is that access to lithic raw materials would have been relatively easy..." [2]. Which

agrees with Chace's comment of a large encampment that had been there for years (it was in fact a year round camp and would be large and have plenty of tents) and the manufacture of arrow heads.

The date 2,500 BP for the site makes it unlikely that the remains described by Chace be those of a "Christian". So, to whom did they belong?

Ancient Mariners...

Since Native Americans did not know how to produce steel or iron tools, the owner of the 18 inch rapier 500 years BC, must have come from some steel making culture from Europe or Asia.

I am reluctant to pronunce myself in favor of a Phoenician, Greek or Carthaginian because I am not sure if they made steel swords (they made them of iron). Of course, Chace may have mistaken iron for steel, in which case the owner could have belonged to any of those cultures.

Steel, is iron with a certain -very low- content of carbon. The resulting alloy is more flexible than iron and does not shatter upon impact. It was not easy to make, and very valuable.

How did this person get there?

Lake San Martín is quite inaccesible from the West: a shipwrecked sailor on the South Pacific coast of Chile would have to walk along the northern edge of the Sothern Ice Field, up the dense forests of the Pascua River and then

after reaching the lake, sail its choppy waters to its Eastern coast (or walk through a terribly dense forest with sheer sloped mountains). The terrain is so bad that even today there is no road linking the Chilean town of Villa O'Higgins on the north tip of the lake with the Argentine side of the border.

From the Atlantic, the lake can be reached either from the mouth of the Santa Cruz River or from San Julián inlet by following the Chico or Sheuen River to its

sources and then, across the divide to lake Tar and along Tar river till reaching Lake San Martín.

The fact that it is a rapier (thin and narrow sword) and made of steel may even make it possible that its owner was a Spaniard, from the XVIth century. In which case the date is wrong, instead of 2,500 BP, it should read 500 BP.

This was an area beyond civilization, Spain never colonized or conquered Patagonia, so the Spaniard may have been a survivor of one of the many shipwrecks along the Strait of Magellan or even from the ill-fated towns founded on the Strait by Sarmiento de Gamboa in the late 1570s.

Maybe the unfortunate man walked north, seeking the Spanish settlement on Chiloé Island, marching close to what is now the border between Chile and Argentina, on the edge of the forests, going

around Lakes Argentino and Viedma, and then following the native path towards Lake San Martín, where exposure, hunger, illness or maybe a band of natives, ended his pain.

This last theory (the "trekking Spaniards") is not as crazy as it seems: in 1563 two Spaniards (Pedro de Obiedo and Antonio de Cobos) arrived at Concepción, Chile in northern Patagonia.

They swore that they were sailors of a ship that sunk in the Strait of Magellan in 1540, part of the Bishop of Placencia's fleet [3]. They reported that the stranded crew had marched north, confronted the Indians that attacked them,

found a secluded spot and set up a fort. They later lived in peace with the Natives. This was the mythical Lost "City of Ceasars". However Obiedo and Cobos committed a crime and fled north to escape punishment, walking all the way to the Spanish town of Concepción.

There are other instances of shipwrecked sailors: Juan Ladrillero's expedition (1558) capsized in the Strait of Magellan and all were lost except for Lardrillero and a sailor who "with notable courage

and perseverance walked along the slopes of the mountain range, beating infinite difficulties and continuous risks to their lives, reaching Valdivia [in Northern Patagonia] after one year and four months" [6]. (Quite a long walk indeed!).

Sailors from English, Dutch and even American ships (after 1776) ships were also shipwrecked along Patagonian shores: Darwin reported castaways rescued during the voyage of the Beagle, close to Chiloé Island [4], and Wager was stranded on an island for weeks until the natives helped the survivors of his group to reach Chiloe. [5]

Sources

[1] Robert and Katharine Barrett, (1931), A Yankee in Patagonia, Edward Chace Houghton Mifflin Co. 1931. pp. 91-92

[2] Espinosa S, Belardi J, Barrientos G and Carballo Marina F. (2013), Poblamiento e intensidad de uso del espacio en la Cuenca del lago San Martin (Patagonia Argentina): nuevos datos desde la margen norte. Comechingonia vol.17 no.1 Córdoba jun. 2013.

[3] Patricio Estellé and Ricardo Couyoudmdjian, (1968). La Ciudad de los Cesares: Origen y Evolución de una leyenda (1526-1880). Historia, No. 7, Instituto de Historia. Univ. Cat. de Chile. 283-309.

[4] Darwin, C., (1987). The Voyage of the Beagle. Ware: Woodsworth Editions.

[5] Gurney, A., [Ed.], (2004). The Loss of the Wager: The Narratives of John Bulkeley and the Hon. John Byron. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

[6] de Rosales, D., (1666) Historia General del Reyno de Chile Ed. 1877, Imp. El Mercurio., Vol. 1. pp. 84

Patagonian Monsters -

Cryptozoology, Myths & legends in Patagonia

Copyright 2009-2014 by Austin Whittall ©