I will continue with the Second Part of my

Previous Post.

A very deep and well documented paper was written on the possible survival of native American horses in Argentina until the mid sixteenth century. Its title "Antigüedad del Caballo En El Plata" (The Antiquity of the Horse in the River Plate), and its author: Anibal Cardoso. [1]

Cardoso tackles the matter from different angles, which I will summarize in this post:

The Source of the horses

According to the orthodox view, when in May 1541 the Spaniards abandoned the first town that they had established on the River Plate (the first Buenos Aires, founded by Pedro de Mendoza in 1536), they left behind 5 mares and 7 horses. They burned the settlement and moved up the Paraná River to Asunción in Paraguay.

They had decided to leave because there was no food and the natives were hostile. Paraguay was warmer, food was plentiful and the natives were peaceful farmers.

Then, in 1580, the settlers in Asunción needing a port on the coast, returned downstream and built a second town (current Buenos Aires). They saw many horses and mares, tall as mountains all along the coast, for 80 leagues (400 km - 250 mi) and inland, up to the Andes.

So, the official version is this: these 12 European horses bred in freedom, roaming the Pampas and in 40 years filled it with hundreds of thousands of wild ponies.

Cardoso disagrees

This account of the "abandoned" horses was written in 1612 by Ruy Díaz de Guzm&aactute;n. But the official accounts written during the settlement of Buenos Aires and the relocation of its inhabitants do not mention it.

Ulrich Shmidl, a German mercenary who came to Argentina with Pedro de Mendoza in 1536 wrote a detailed account of his life in the first Buenos Aires and later on in Asunción. They literally starved to death, they ate rats, snakes, the corpses of executed prisoners, the soles of their shoes, and of course, their horses. Possibly none survived.

When they left for Asunción in 1541 they burned the town to leave nothing to the bellicose Querandi natives. So any surviving horses which were used in combat, would not have been left behind.

They did leave pigs on an island in the River Plate (San Gabriel), and left specific instructions about them. But not one word was written about horses.

The documents at Asunción do not mention horses until the arrival of Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca in 1542. So, none were brought from Buenos Aires. All had been eaten by the starving inhabitants.

Cabeza de Vaca brought 27 horses with him. And they were an expensive item, worth 4,000 gold Reales. A fortune. In 1547 only 26 were still alive. But in 1553, Asunción had 130 horses!. These must have been provided by the natives, in exchange for Spanish goods. The horses were native ones, from the Pampas.

The Horses were local ones

Cardoso says that the Spaniards at Buenos Aires did not see horses in 1536 - 41 because the Querandi hunted horses, so the animals just moved away from the coast, inland. Furthermore, the coastal jungles were home to jaguars which preyed on the horses. This led to very few horses along the coast.

Later, in 1580, the Spaniards returned in force, they repelled the Querandi and advanced inland. That was when the came across the horses, vast quantities of them. Native American horses.

The Spaniards however said that these horses were the offspring of the ones left behind by Mendoza. Why? To avoid paying taxes to the Spanish King.

The Royal Tax Collectors said that the horses belonged to the King as they were part of his domains. But, after going to court, the judge found in 1596 that since they were the descendants of horses brought by Mendoza in 1536, they were not "of the land", but feral horses and therefore exempt of taxation.

The Spaniards knew about the horses from the natives, they knew that they were American horses and not European ones gone wild, they made up the "Mendoza's horses which ran wild" story just to avoid paying taxes.

The natives had never seen a horse and were frightened by them

Not so! says Cardoso. Ulrich Schmidl wrote about a battle between natives and Spaniards. The former used bows and arrows and also Boleadoras, with which they entangled the legs of the horses making them trip and fall.

Boleadoras are basically a rounded stone wrapped in leather to which a long braided cord of leather is tied. The tip of the cord is whirled around the head of the thrower, and released.

One single stone is known as "bola perdida" (lost stone ball) and was used to knock an enemy on the head, killing him. Also to hunt. The stone hit and maimed.

Two or three stones could be tied into a "V" or a "Y" configuration and whirled. The 2 or 3 cords wrapped around the hind quarters of the prey, causing it to fall.

Different stone sizes were used for different prey. Heavy stones were used for large animals, i.e. horses. Light stones for the American rhea (ostrich like) and the guanaco and deer.

The Querandi and the Chilean Araucanian - Mapuche natives fought the Spaniards in bogs, where their horses stuck fast in the mud. They evidently used this technique in the past to hunt native horses; they knew their prey and were not frightened of them.

Physiological similarities between the Argentine Creole horse and the Hippidion

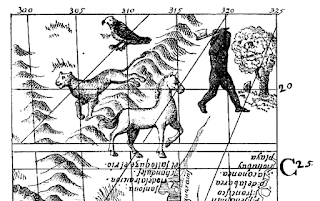

Cardoso cites a Professor Van de Pas, who compared the anatomy of an Argentine Creole breed horse with other modern horses and also prehistoric extinct ones. His findings are surprising:

The Creole horse has its fingers II and IV mor atrophied and the main metatarsals are highly compressed, laterally, and resemble those of the Hippidion which was a South American horse whose fossil remains are found in the Pampas during the megafaunal period.

The image compares the bone structure of a modern European horse, the modern Argentine Creole horse, an ancient Old World fossil horse (Hipparium) and the recent Argentine fossil Hippidion. Notice the similarity between the Creole horse and the Hippidion leg bones and the difference with the European ones! If Creole came from European stock, why would it resemble the native (allegedly extinct) horse?

Comparison of the toes of Modern European horse, Argentine Creole horse and prehistoric horses (Hipparion and Hippidium).

We will carry on with his analysis in our next post.

Sources

[1] Anibal Cardoso (1912), Antigüedad del Caballo En El Plata. Anal. Mus. Nac. Bs. As., Serie III t. xv. Marzo 4, 1912. pp 371+ Read the article.

Patagonian Monsters -

Cryptozoology, Myths & legends in Patagonia

Copyright 2009-2013 by Austin Whittall ©

/>

/>